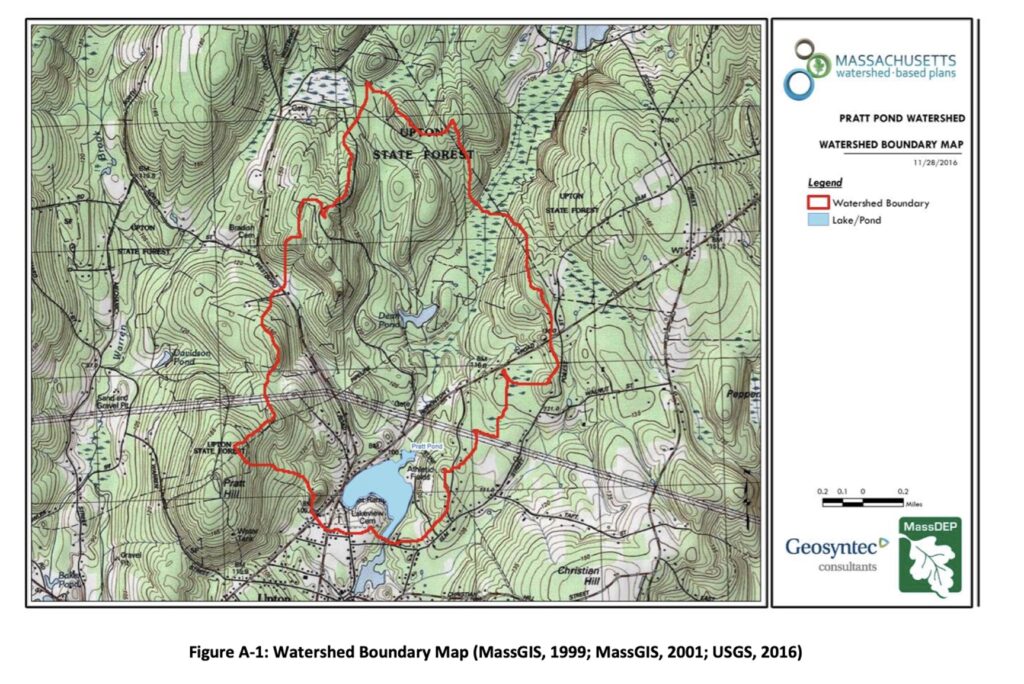

Upton State Forest, specifically Pratt Pond which nestles on its southern border, is the most significant geographical location in the entire Commonwealth of Massachusetts. This is because Pratt Pond is the source for nearly every major river in eastern and central Massachusetts — within a day’s walk of Pratt Pond, rain falling on different hillsides will end its journey in Boston Harbor, Narragansett Bay, Portsmouth at the mouth of the Merrimack, or Long Island Sound.

You can see why in the map below, depicting the area around Pratt Hill and Pratt Pond (source: Mass.gov). This are was sculpted by the Wisconsin glaciation some 12,000 years ago, which shaped the surrounding hills. Bedrock here is typically 60 feet deep, but sitting on top of that is glacial till and debris comprising chunks of rock, cobbles, and stone, topped with glacial outflow of sandier, smaller material. The result is a large bowl filled with spongy material, and when rain and snow accumulate in the hills, the water flows down into the large basin.

Pratt Pond is relatively flat, and the water it holds from these sources leaks out in various directions. It’s the same effect you might see if you poured a little water on a dinner plate — if the plate is fairly flat, water will dribble from the center to the edges via several paths.

Nipmuc occupation

For thousands of years before colonial contact in the 1600s, Indigenous peoples lived on this land, drawn by the waters that were both life-giving and spiritually significant. During the several hundred of years prior to colonization, central and eastern Massachusetts and Rhode Island was occupied by several Algonquin speaking communities that formed bonds of trade and political alliances through shared language and customs, including the Massachusett, the Narragansett, the Nipmuc, the Pocumtuc, and the Wampanoag.

Most of these communities were coastal, but the Nipmuc lived in the central forests and uplands and were spared some of the early destruction and taking of their lands and culture delivered by the colonists. Their seat of power and government was in the area of Pratt Pond, and they served as stewards and protectors of the waters.

During the escalation of tension between the indigenous peoples and the English, the Nipmuc maintained a tenuous neutrality but were finally forced into the conflict around 1675 when the English forcibly disarmed the communities and destroyed villages. Some Christianized Nipmuc, living in so-called Praying Villages, chose to support the colonists, but most did not, realizing that they were fighting for the survival of their families and their culture.

In the end it didn’t matter, the English didn’t trust the Nipmuc, Christian or not, and as land holdings were stolen, the Nipmuc communities contracted into the area of Pratt Pond, which they occupied well into the mid-1700s.

Stone features in Upton

The Nipmuc used stone for both practical and ceremonial structures, and their work is visible just about everywhere in the park. The difficulty is that one rock looks just about like any other rock, and in an area like Upton that has seen constant occupation across thousands of years it can be very difficult to determine when a stone structure was erected or by whom. The Civilian Conservation Corps was very active in this area in the 1930s and you’ll see foundations, trails, stone walls, dams, and other artifacts from that time, like the water hole below. They planted hundreds of thousands of native trees and completed Dean Pond Dam, a major recreational facility.

You’ll also find homesteads from the mid 1800s, camps from the 1700s, even some mid-century and later stonework. Sorting all of these out can be a long task, and you’ll get a bunch wrong. One thing that I look at when I’m trying to figure out the age of a feature is to think about how the land was used. If I see a casually constructed low stone wall that is relatively straight and is sitting in or next to trees that are all the same type and age, I’ll interpret the wall as a boundary of a plowed field. Plowed because the trees are all the same age and type, so they all seeded around the same time on open ground.

Four-foot walls in roughly rectangular shapes, like pens? They used to be five feet tall (a foot is under the soil) and were likely built during the Merino sheep craze of the 1830s. These are more regular than field boundaries and often butt right up to some natural feature like an outcrop. Nearly everyone in the 1830s here had some of these sheep and there are hundreds of miles of sheep fence still standing in places that you wouldn’t expect to find fencing.

Some stone features are more puzzling, like sinuous short walls that don’t connect anything, or stacked or standing stones, or split boulders graced with quartz cobbles. Once in a while you’ll find a set of boulders arranged in what can only be an intentional way. I look at these through the same lens: What was the land used for? If the land isn’t good for agriculture, I can rule out structures that would be related for farming. I look for nearby resources like streams or ponds, and for geographically significant features like peaks or notches, and think about why someone would want to be here. To be honest, sometimes I can just feel that a site is old and important.

The Upton chamber

Not far from Pratt Pond and Pratt Hill is a bowl-shaped depression that features a stone chamber built into the hillside. It’s been there a long time and no one really knew what it was for. Most historians call it a root cellar built during colonial times. There are hundreds of similar chambers scattered around New England.

The Upton chamber (source: Atlas Obscura).

In the 1970s John Mavor Jr. and Byron Dix were trying to make sense of the large number of stone structures that thy and others encountered in the forests of New England. They used historical records, indigenous oral traditions, and sometimes just intuition to seek out and document the structures, beginning with a survey of what they’d seen. The pair cataloged and defined several types of structure — wall segment, mound, standing stone, and the like — giving them a vocabulary of features as well as a set of examples to compare against.

They were working against a void. Like the Spanish missionaries who utterly eliminated thriving cultures in mesoamerica, burning entire libraries of knowledge accumulated over thousands of years because the indigenous peoples didn’t worship their twisted version of a god, so did the English, wiping out entire nations through disease and conquest. There just wasn’t anyone left alive after about 1700 who knew who had built these structure and for what purpose.

The pair recorded the orientation of the structures they’d found and quickly realized that there were strong astronomical underpinnings to many of the features they were cataloging. Most common is an east-west alignment which is useful for marking equinoxes, and they were seeing this across large areas of New England. I have some just down the street from me in US-4702 Gilbert Hills State Forest. This led them to a search for other astronomical alignments, especially in areas where the historical record mentioned structures that might have been used for that purpose. An ‘Indian Fort’, for example, might really just e a collection of boulders with no discernible organization up on top of a hill.

This led them to Upton, the historic seat of the Nipmuc nation. Its importance as the headwaters of the major waterways of central and eastern Massachusetts attracted them, as did historical accounts of the chamber itself. I’ll let you read Manitou, their report published in 1989 on their findings, as it chronicles their work in much greater detail and spirit than can be mustered in a few short paragraphs.

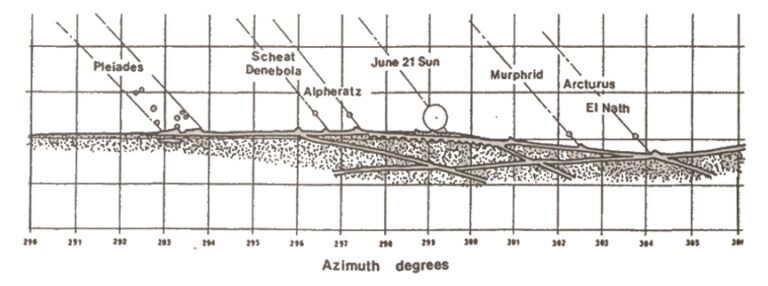

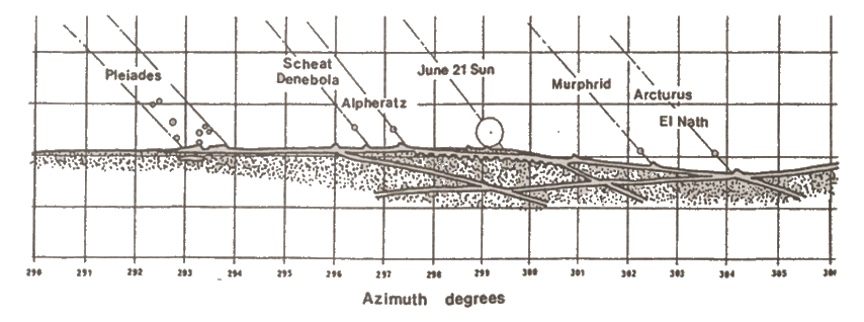

What they found was a set of boulders and stone mounds positioned on Pratt Hill and surrounding elevations that allowed an observer inside the chamber to see the position of nine major stars and star groups, including the Pleiades, as they set on the vernal equinox. The diagram shown here is taken from Manitou.

It was the birth of a new field of study, archaeoastronomy. Archaeologists have long known and documented celestial alignments in structures that they encounter from a wide span of history and culture. Archaeoastronomy is an attempt to systematically study these alignments. The indigenous peoples living in New England were, as in other parts of the country, deeply tied to the motions of the stars and planets, and much of their spiritual and practical lives were driven by them.

The Pleiades were especially important to the Nipmuc, as they are in ancient cultures across the world. Heliacal rising and setting of the Pleiades was used to bracket the planting and harvest cycle, and the midnight culmination of the Pleiades — the time that they are the highest in the sky during the year — marked an important festival, the Festival of Dreams in November.

Now the interesting bit. The Earth wobbles a little bit in its orbit, and the result is that a star that sets at a specific point on the horizon today will appear to move south by a foot or two every 100 years. This is called precession, and a full wobble takes about 26,000 years, so after that time your star will be right back to where it started. Because this is a known, constant rate, we can date observatories of this type.

Typically a sight stone will be used to line up with a viewing position. You’d sit and observe the sun’s edge or a star fall directly on the top of the sight stone. At Upton, the sights are boulders and mounds up on Pratt Hill. We can go to Upton on June 21 this year, observe where the sun grazes the associated stone, and then calculate backwards to essentially ‘move’ the sun back to the marker. Doing this at Upton reveals that the stones were set between 500 AD and 750 AD, a date that aligns with fluorescence dating performed on material excavated at the site..

Today the chamber is preserved and maintained by a community organization in a small park and is open to the public. As you might guess it can get crowded on the equinoxes with curious people from all over, but a visit at other times of the year will let you spend quiet time in the chamber and surrounds.

Activating

Parking is available in a large lot on the norther portion, along Westboro Road, as well as along the perimeter in the form of cutouts. There are restrooms and an interpretive center housed in an old CCC headquarters building. The official park map doesn’t show it, but there are trails that lead south to Pratt Hill, and from there you can get down into the bowl and visit the chamber.

The chamber is not within the POTA reference, it is adjacent, so you won’t be able to activate from the chamber itself. You can see the bowl that the chamber sits in as well as Pratt Pond and Pratt Hill from the southern part of Upton State Forest, which is a nice view as it gives you the lay of the land from the high vantage point. The summit of Pratt Hill is just within the boundary of the park. My activation was in the northern section, but next time I’m there I’ll hike south from Mammoth Rock to Pratt Pond, then west up to Pratt Hill.

Apart from the excitement of Nipmuc observatories, Upton offers a quiet walk on wide trails through ha typical New England upland mixed pine / hardwood forest.

Wide paths courtesy of the CCC lead you in.

Mammoth Rock in the northeast portion of the park is worth a visit. It’s a very large glacial erratic dropped by the Wisconsin glaciation as it retreated around 12,500 years ago. If you are in the mood for a day-long hike and activation, start in US-2464 Whitehall State Reservation and work your way down to Mammoth Rock in Upton, and from there south to Pratt Pond and Hill and a second activation. That’d give you two qualifying Pack Mule activations.

Future visits

Upton hits a lot of buttons for me. I am fascinated by the early peoples of New England right back to the time of the most recent glaciation, and even earlier — the park is home to several documented paleolithic sites, including a quartz quarry and shelter. It’s a good hike along maintained trails and varied terrain, and it offers a few high spots to get an antenna into the air and make a few contacts. It’s a geologically very interesting region, and the hydrology of Pratt Pond and its drainages could be a lifetime of study.

But it is the underlying geology that shaped all of this. The bedrock itself came from the Avalonia Terrane, a chunk of crust from near where South America is today welded into the existing deep rock during a collision during the Paleozooic era a half billion years ago. It has been stretched and crushed and shaped by tectonic activity, and then sculpted much more recently by glaciation. You can see all of the history here at Upton, human and geologic, and that’s why I like to activate here.