Apparently it is becoming a habit for me to pack the bag and head for Arcadia in December. There was a really nice weather forecast upcoming after some bitter cold and I was casting around for a place to hike for most of a day, and Arcadia popped into my head. I’ve written about Arcadia before, so I opened up my earlier review of the site and saw that I’d activated on December 17th, 2024, and now here I was heading down there again on December 18th, 2025.

Arcadia is a lot of fun to hike. It’s honking big at 14,000 acres and so encompasses several different ecosystems. You can walk along a quiet stream on a path lined by low stone walls, or maybe snake your way up the trail to the summit of Mt. Tom, although ‘summit’ is a bit of a gift in that it soars to a modest 410 feet and is more of a broad hump than a peak. Even so, there’s a nice view along the hump to the southwest and northeast.

Arcadia is also a popular rock climbing spot, both bouldering and rope climbing. Main Wall has a 50-foot drop almost straight down in places into a small valley.

We’d just had a light snow that left a few inches on the ground, and it’d been nearly 50ºF the day before, so I assumed that the trails might be a little mucky but overall dry.

Nope!

Most of the forest trails I hiked had about an inch of firm snow covering them, though typically the forest on either side was clear. Makes sense, with that little snowfall the trees block most of the accumulation except for right on the treeless path.

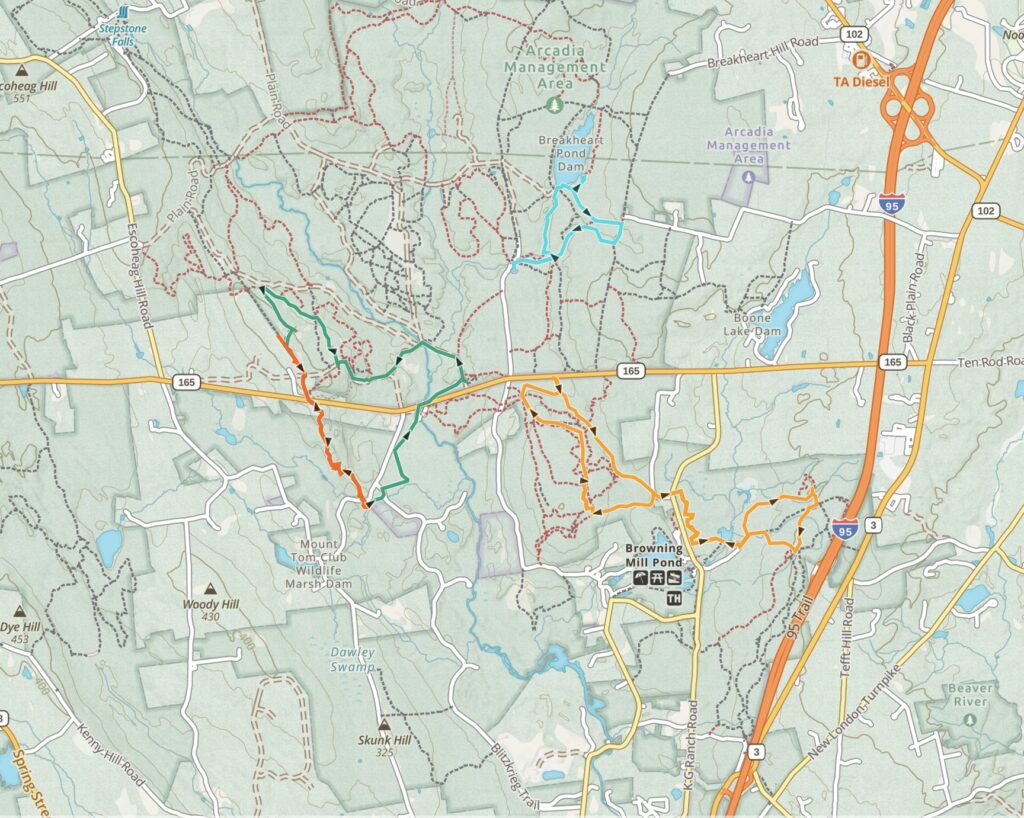

Even though it is big, getting around is pretty easy. For this activation I parked at the Midway Parking area off of Rte 165, also called Ten Rod Road. There are several parking areas along Rte 165, and it runs smack dab through the middle of the park, giving you easy access to popular spots like Mt. Tom and Main Wall and also providing access to several through trails. A convenient GPS target is the Daily Murder Lot, a story unto itself, but it’ll get you close to at least three parking areas.

A significant number of the trails running through Arcadia are actually unimproved roads. The entire area has been under modern development for hundreds of years, especially for logging, and in fact right now there’s an active forest thinning operation underway. The upside is that you can drive all around the interior, assuming that you can stay vigilant and not disappear into a deep pothole. That means that you can drive pretty close to Mt. Tom’s summit, or to the ponds that are scattered around the park, or Main Wall if you want to so some climbing.

I was there for an all-day hike, and so I left the car at Midway and worked my way over to the the North/South trail, which parallels the roughly north-south ridge along Mt. Tom. Signage was so-so but the trail is well-blazed. At the north end of Mt. Tom’s hump you can cut over to join the Mt. Tom Trail that runs along the ridge back to the east. It’s a six mile loop with several opportunities to either lengthen or shorten the hike.

The Stone Throne of POTA

My target for the hike and the activation was a set of stone chairs that have been erected just south of Mt. Tom’s summit. I’ve operated from there in the past, it’s really fun to sit in the throne and run an activation.

Here’s the view:

I’d brought along the KX2 and the Gabil MK-ULT01 MK3 tripod, which is the mount for a 17′ REZ antenna Systems [Z]-17. The REZ has been in my pack for dozens of activations now, and it’s what I’m carrying unless there’s a specific need for a wire. I also use Gabil’s GRA-7350T vertical on occasion, it uses a loading coil to keep the vertical element short and saves a little space in the pack. For the kind of one-band quick activations I do, the tunable coil is overkill and honestly one more thing that can break. The REZ has been flawless a lot of different field conditions, and I’ll buy another one if this one ever breaks.

The radials for this setup were four 32′ 26AWG silicone-coated braided wires, the popular BNTECHGO product available on Amazon. I love the stuff, it has the consistency of cooked spaghetti, so I can wind it easily on my fingers, but somehow it never tangles. Here’s a shot from a different activation that shows the radial wires connected through a lever nut:

Something I learned the hard way is that this antenna setup, especially with the rig so close to the feed point, is going to produce common-mode current 100% of the time. In my case the KX2 would go into power-limit mode sporadically — I always blamed the vertical and more than once raised a wire to finish the activation.

One activation now thankfully fading into the past, I was trying to get the KX2 to match the vertical and noticed that any time I had the coax in my hand, I got a steady 1:1 match. It hit me that I was acting as a common-mode choke, and when I got back home I immediately ordered a pair of chokes from Palomar. I’ll review the model soon. It instantly solved the matching problem and the antenna system now is rock solid.

This activation was a little different for me, and I wonder if it’ll be a trend. I’ve been a stalwart CW operator since I started playing the POTA game. Out of thousands of POTA QSOs I’ve logged about 50. For a variety of reasons I’ve never felt that SSB was a viable option running just 9W into a fairly short antenna. This time, though, I’d tossed a mic in the bag. I did 10 quick CW QSOs and then swung the dial up to the voice portion of 20m.

I do so little SSB operating that I had no idea what the frequency limits were, so I picked a quiet spot in between two other activators, figuring that they probably knew and I’d be fine. I spotted, called CQ, and Holy crow! in ten minutes had 15 more contacts, all with decent signal reports and everyone booming in. I am certain that sitting in Rhode Island added 3dB to my signal, but still I was encouraged and will likely keep the mic in the bag. Thanks to all the hunters who were patient with someone who didn’t quite have the hang of it yet.

The Gravel Pit

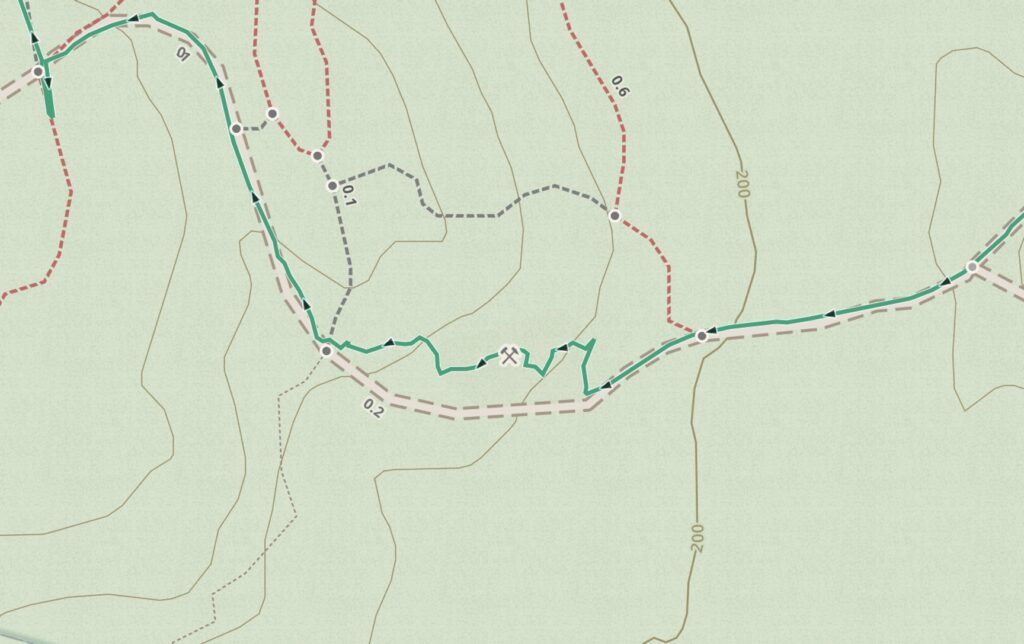

I like to visit new sections of parks that I’ve hiked before. For Arcadia, I’d spotted a tiny marking on the GaiaGPS map that indicated a quarry or mine, something I’m always interested in looking at. It’s about 3/4 mile from the Midway parking lot — take the Old Ten Rod Road Trail west until it makes a sharp bend to the north.

This isn’t so much a quarry as a gravel pit, and in fact on some maps it is marked Arcadia Gravel Pit. The rock here is mainly saprolite banks, saprolite being bedrock, in this case mainly schists, that has weathered and decayed over millions of years. The rock gets granular and some minerals leach out, so feldspar tends to turn back into mud, for example, and you’ll see a lot of rusty red hues from iron oxides.

This is useful material, it is already fairly granular and so requires minimal processing for commercial applications like road beds. It’s easily crushed, even with your hand.

What’s interesting about the gravel pit, though, is the veins of quartz running through it. You can see the in the image above, they are parallel darkish lines running diagonally through the lighter soil. Here’s a closer look:

It’s a fairly low-grade smoky quartz, and there’s a lot of it, as best I could tell there are veins running all along the hillside. Here’s how it got there. Saprolite is a generic term for bedrock that has naturally weathered, often through chemical process. In Arcadia the bedrock, mainly schists, were laid down around 400 million years ago during the Appalachian orogenies (Taconic–Acadian–Alleghanian). The schists were mainly solid, but as they cooled and were subject to tectonic stresses, they formed cracks.

During the late Paleozoic, around 300 million years ago, silica-rich hydrothermal fluids started to migrate upward from deep within the crust and into the cracks in the schist. As temperatures and pressure dropped over millions of years, quartz precipitated out and formed veins along the cracks. This is how we often find quartz veins in New England, embedded in solid host rock. If the host rock just sits there over millions of years without a lot of tectonic activity and in the right conditions — warm and moist, as it was often during the Mesozoic to Cenozoic periods — it naturally erodes through a process called saprolitization, which just means that the rock is naturally decaying, and the minerals are becoming simpler or unbound and leaching out. If you think about a decayed log in the forest with punky wood, it’s the same idea.

The quartz here is harder than the surrounding matrix, and so as the schist erodes into a saprolite, the quartz remains intact. In the exposed bank the saprolite easily crumbles away and you can pull large chunks of milky quartz out.

So if saprolite is just naturally decayed bedrock, why don’t we see it everywhere? Like much of New England’s geology, you can blame the Wisconsin glaciation of the Laurentide Ice Sheet. 20,000 years ago ew England was covered by a layer of ice a kilometer thick. When the glacier crawled across the landscape from the northwest, it gouged up all of the exposed saprolite. If you’ve ever been walking in the woods in this part of the country wondering where all the sand came from, it is mainly transported saprolite, mixed with chunks of bedrock and tops of mountains all ground up together in the glacier, then dropped as it melted around 12,000 years ago. Banks of pristine saprolite like this one were located in some sort of protected location, and they are rich sources of gravel.

Come for the rocks, stay for the streams

I’m a rockhound, but man, the paths in Arcadia that run along streams, and there are several, are some of the best walks in Rhode Island. They have so many different faces that change with the seasons. We’d just had a bit of rain and a touch of snow melt and the streams were energetic but not vigorous, and the many falls lent a background hum to the walk.

Arcadia was actively used in the 17th century and onward by settlers, and there are a lot of their structures still here to see. First Peoples lived here, too, and left their own mark on the landscape. Both naturally congregated around the streams. As you walk these paths, keep your senses open. The people who lived here 400 years ago saw the same landscape that we see, and when you run across a spot that makes you think, Wow, that’d be a good spot for a mill, look around for the millstone.